Ehdrigohr has been the beginning of many interesting discoveries and journeys for me over the last few years. When I set out to make it I was never quite sure what it would end up being. I didn’t know what I would end up finding in it. More importantly, I wasn’t sure what would appear within it and find its way out into the real world.

It came together, more and more, as I came to understand my needs as a person and a designer. As I realized where I was coming from, and what issues I wanted to attend to, that led to a variety of things finding voice and gaining life. As a result, there is a lot of stuff crammed within the 400+ pages of the book. Some very well thought out and others that are not as clear as I’d like.

One of the pieces I’m especially proud of is the character creation process called the “Winter Counts.” I wrote about them early on here . Essentially it is a mishmash of the old idea of phases that are in many Fate based games, some of the big ideas in Ehdrigohr’s core narrative, and some Lakota tradition that’s part of our cultural narrative. In the real world, winter counts (or waniyetu wowapi ) are basically a way of keeping the histories of the people. You can see an example of one at this page.

In Ehdrigohr they become about acknowledging the struggles of the characters the players will play and creating a group history. In Ehdrigohr the year is named “The Winter of. . .” and extra details are given to that title to provide a more poetic recounting of the timeline. When players are finished they have 6 winters that define their course through the world up to the point where the game starts. These winters are significant memories and represent defining moments in the character’s growth. From the winters we extract the traditional Fate aspects, but the winter remains as a memory thing that fuels the aspect. In points of dramatic tension a winter can be “burned” to give a boost to a character and their friends, but then the winter is not available for a while. This also temporarily removes access to the associated aspects and abilities connected to it until the winter resets at the end of the story.

I’ve come to love the Winter Counts process because every time I’ve done that portion of character creation with a group of people, I found myself impressed by how affected they were by it. There was such buy-in and camaraderie among players and they felt an extra connection to their characters. They were notably anxious to embody this person that they had gotten to know through this process. There was a real connection established between the players and between the players and their characters. That got me thinking that maybe there was more to this process than I had originally thought. As I metabolized what worked, and didn’t work with it outside of the Ehdrigohr narrative, this process found its way out of the game, and into the real world, as part of my bigger work of telling stories and getting people to tell their stories and see the narratives that affect them in the world.

About a year after I finished Ehdrigohr, I ran a few sessions with some kids at the American Indian Center and some folks in the community started talking about it. Eventually the Title 7 program here in Chicago reached out to me asking if I would come do a workshop with kids they had in their winter break program. This was in conjunction with, and located at, the Ho-Chunk Nation’s Chicago branch office. They were trying to find ways to connect children and families to traditional ideas and ways of seeing the world. Apparently, they were looking to talk about Winter Counts and someone remembered that I used to talk about them and used them in my games.

When they asked me to do a workshop on Winter Counts I had to stop and ask myself what could I possibly do that had any meaning and would stick with people. I knew most of them wouldn’t want to make characters for my game per se, and just talking about winter counts as an academic sharing seemed boring and disconnected. What I decided was to try just removing the winter counts experience from the game altogether and turn it into a family exercise. My thing has always been getting people to play with their cultures, touch traditions, and make them relevant to themselves in the now. This seemed like a perfect opportunity to engage that belief.

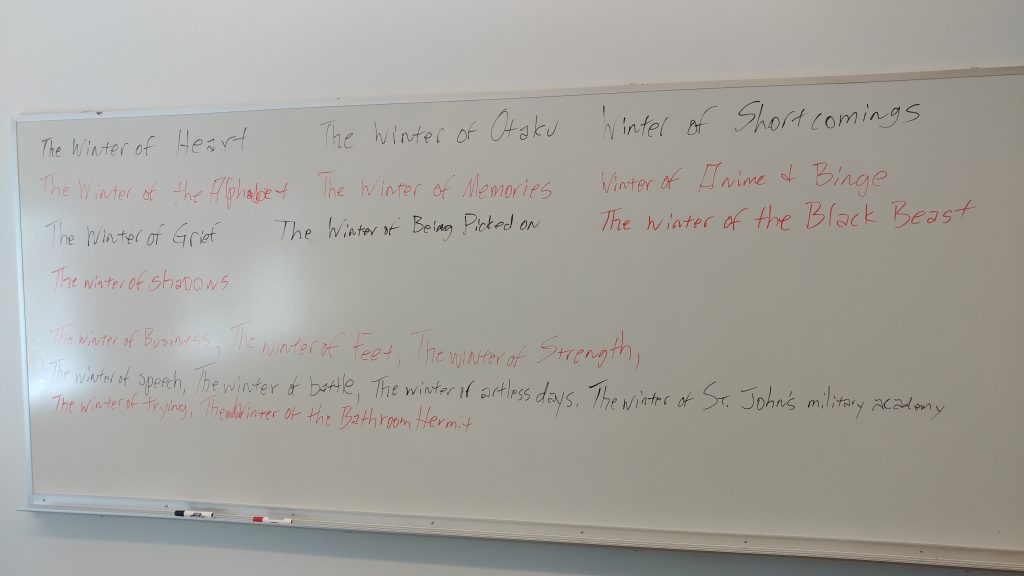

What I did was do a short breakdown of the real world, traditional version of the winter counts, and then I used the process from the book to get families making personal countings of big moments from their lives. I had a number of moments of interest, taken directly from the game, that I used to facilitate how I wanted them to move through the process. They guided what pieces of their life they were to be looking at. Each of these stages was an opportunity to jot down an important moment in their life and then poetically name it The Winter of something. So a point where someone was losing an elder might have been named something like “The Winter of lost Grandmothers” or something in that vein.

We then got people to tell their winters and describe their stories and it was interesting to see how some events showed up in families from different perspectives named completely different things. In some cases, there were things that people hadn’t shared with each other as family members. Notably this came more from the children who had fears that they had not shared. The wonderful thing that came out of this process was that people began talking and sharing stories of self, family, and tribe.

I was terrified, going into the presentation, that it wouldn’t work and people would be disinterested. I was very happily surprised to see how effectively and powerfully it worked. This was something I would never have done were it not for having shaped it first as a part of my game. I felt, however, that something was missing with the process but couldn’t put my finger on what. So I left it alone to simmer in my brain for a bit.

It wasn’t until I was doing character creation during an Ehdrigohr presentation for the Future Imaginary at Concordia University that the missing piece began to manifest. When people went through the winters process in the game it was as a beginning. When you were done it wasn’t about seeing where you had been but setting a foundation for where you would go. It was a moment of design. What was missing was that I had approached the process with the families from the point of view that it was about looking back. While looking back was a part of the process the intent was creation and beginnings. So I started thinking a bunch about how I could bring that creation experience to the fore. Also I felt like I had missed an opportunity to explore the experiences and perceptions of the world that we took from them. When doing character creation we create the aspects and that becomes a piece of narrative that we affect the world through, one scene at a time. Lastly when making a traditional winter count we have images attached to the events that form a visual and tangible connection to the idea. I didn’t really have any of that stuff in the iteration I did at Ho-Chunk.

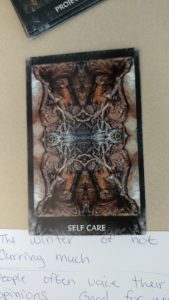

So these thought processes intersected with other thoughts I was having about playing the game in general. Thoughts about not liking the dice and wondering if I could create a card based experience that worked to help people play Ehdrigohr and served a similar purpose to the dice roll while providing a sort of tabletop GUI that helped players to keep track of the various states of play and how aspects were in use. I looked at how various games were using the deck of Fate. While I liked the Deck of Fate, I didn’t feel that it was appropriate to what I was trying to achieve. I looked at a bunch of collectible card games, and then I started looking at various storytelling card games. That led me to look at various older ways of displaying narratives with cards which landed me squarely with Tarot and other oracle cards. I started thinking that maybe there was something there in something like that but I didn’t want the cultural baggage that came with the art typically attached to these. Luckily, an answer to the art problem presented itself quickly. My partner Stacey Taheny, who I was working with in other creative endeavors, namely dance and music making, had this wonderful series of images that she had been making from things in nature. There was a local forest that she traveled through regularly and took pictures. She would follow up by manipulating the photos to create these powerful images that looked like things altogether different.

One day I was looking at the images. I had been talking to her about using one of them for the cover of one of my adventure books and after doing the layout was remarking about how powerful I thought all the images were. We got to talking about how it she wanted to find a way to connect them to Ehdrigohr and I brought up my thoughts about cards. That turned into a conversation about making the Ehdrigohr card game. We couldn’t identify what that was and so just got to making cards to see how they might look and where it would take us.

As the cards came together they revealed this capacity to instigate conversations about what one saw in the cards. The images always had this quality but I think it got magnified by becoming manipulatable items and not stuck as digital images on a Facebook gallery. Just touching them and turning and moving them caused what one saw to change from moment to moment. The Ehdrigohr connection became apparent in the sense that this would be a tool that the Society of Rooks would use to collect painful stories from people that would become tattoos on their body.

As I saw that connection I found myself asking how a Rook would use these cards. This informed the play and instructions I was writing to support the images. Over time the project morphed and grew until it became its own thing in the form of the Arboretum Imaginarium. (Check out the photo albums in this Facebook group to see more Stacey’s work.)

Once this was more fully manifested I began thinking and seeing ways the cards could be used. One of those ways, I realized, was that they would be a great piece of punctuation to the process of the Winter Counts.

By that time I had developed a better sense of how the Winter Counts could be used in an education setting and I saw the cards as part of that process. I played with the idea a bunch in my scarce free time. This past summer the opportunity to try it out came with a summer program I was running at DePaul. This was meant to be an interdisciplinary design program where the inner city, low income kids involved would learn bits of graphic design, game design, writing, and all sorts of ways to express their voices. I wanted a way to try to unify the kids early on and decided I would try a combination of the Winter Counts with the Arboretum Imaginarium. There would be some key differences in how I approached it this time in comparison with the last. It was not about where you have been and how you’ve been affected. It was about what you wanted to create and how you wanted to design yourself and be heard in the world.

So I sat down with these kids and presented to them some ideas about how we carry these lenses around with us like a set of glasses, and that they affected what we could see in the world and what we could focus on and create. They got that and then we began to explore where the lenses come from. That was the point were we began the Winter Counts.

The idea was to look at various stages in their life. We were to look at what stuck with them from those moments, identify the quality of themselves that the incident awakened or empowered (whether positive or negative), and then own it as a piece of recreating a narrative of themselves as heroic forces as opposed to just victims of circumstances. They were to name their winters and use the cards to help identify the qualities. They were to come back the next day and use the winters to introduce themselves as heroes, ready to enter a circle of warriors and creators. They also each were to bring music to be their theme music.

I was worried that the kids would see the whole thing as strange and hokey, but they really embraced the idea. They dove head first into telling their stories and sharing their qualities. They became proud of their winters and when they came back the next day they there was a ceremony, rite of passage, of receiving them into the circle. It was so powerful it bought me, and them to tears a few times.

What was even cooler was the bonding from that process was very real. We had tribe from that day onward. There was a trust among them that was strong. One of the kids made the comment that it was like they had become like best friends overnight. It really helped me to see where they were coming from and how to get them to move to a place of compassion when there were struggles, instead of a place of vengeance and justice.

We revisited these ideas of lenses and qualities, the energy you bring to any situation, and your capacity to change it, regularly. The winters and the cards set the stage for this to be a regular part of our morning check in circle and made it easier for them to talk about themselves. Even the most shy youth found a voice in the circles. It was good.

I followed that experience up by doing a smaller version of it with an all girls group that were part of a different summer program through DePaul’s School of Education. The facilitation narrative of the Winters was more refined by then and we once again used the cards. There was less time with this group so the opportunity to dive into the cards was truncated. Nonetheless, similar sharings happened. They were made more powerful by some of the cross generational sharing that was happening between the young girls and the older women who where their teachers and mentors. That moved my heart.

I was invited to do it a third time through the School of Education with high school teachers. We were doing a more human centered bit of professional development. The winters were focused to be more about their lives and experiences as teachers. Once the winters started coming and people were seeing and experiencing each other’s stories, the whole room loosened up and bit and communication flowed much easier. The teachers were interesting too because I noticed, at first, a resistance. This resistance was more about being worried about doing it wrong, or a perceived loss of stature, or saying something that would get them in trouble. Once they started sharing, the trust began to build and the engagement levels rose considerably.

Now I consider how I can do this with other groups, and in particular, how I can bring it back to my Native circles and engage it again with these more mindful processes intact.